I had visited the gravesite of Orford Township’s original white settlers only once and that was many years ago. Manfred had never been to the site even though he has lived only a few miles down the highway for all of his past 62 years. On an early April afternoon, we walked along the edge of the field and forest to this almost secret spot. Its entrance is marked with a small metal Chatham-Kent Cemeteries road side sign, south of highway 3, just a few kilometers west of the Elgin, Chatham-Kent border (just 5 km east of the Crazy 8 Barn & Garden). At the cemetery lane’s juncture with the highway,

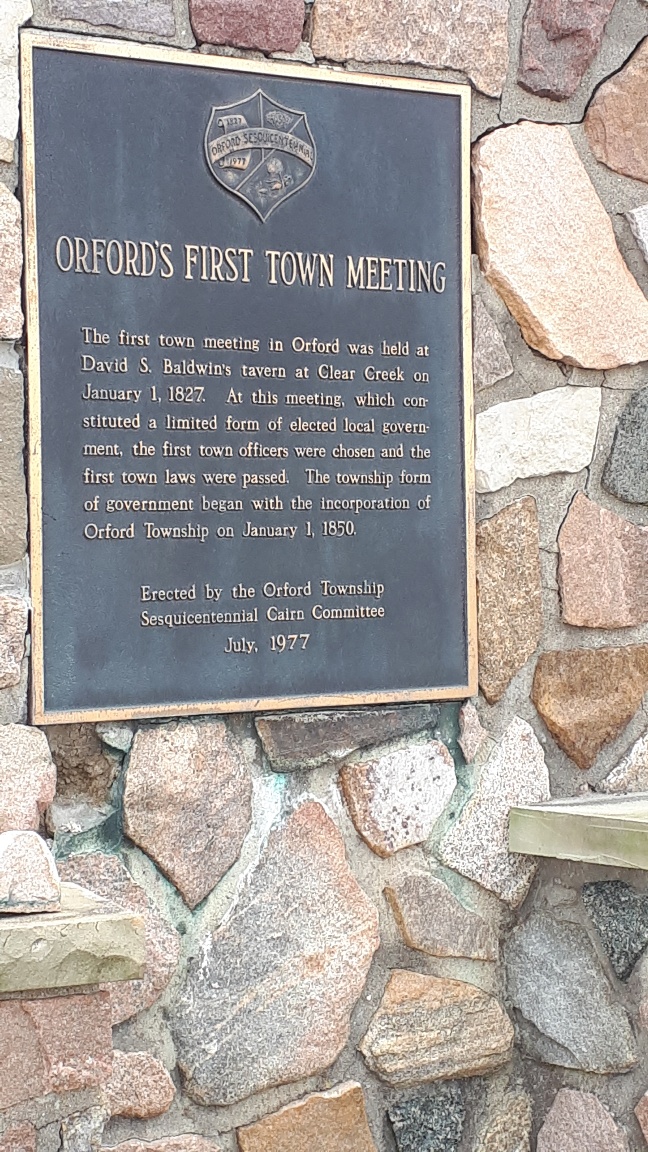

Orford Township First Council Meeting in 1827 is recognized on a bronze plaque on a stone cairn at the entrance to the Bury Cemetery.

there is a stone cairn with a bronze plaque that denotes the first council meeting of Orford Township in 1827. The field stones in the cairn have fractured the cement pointing and threaten to break free on the two front corners. A fence of short metal pipes with a chain swooped between them, protects the monument that guards the path to the cemetery.

The laneway is less than half a kilometer long. I don’t know if it was the laneway into the original farm or whether it was created to maintain the cemetery.

We walked on the grass path between two truck tracks that were filled with spring melt water. The surface of the path was soft under the grass and as we walked, the thawing clay base squished up around the soles of our boots. The imprints of many deer’s cloven hooves spoke of their choice to use the path rather than skirt under the thorny hawthorn savannah to the west of the lane. When puddles overtook the width of the lane, we scooted to the higher outside edges to avoid getting a foot soaker.

The early April Sunday was cool; we were protected from the North wind by a planted windbreak of walnut trees that like perfectly-spaced pickets spread their bare stubby branches above us. With no leaves to rustle, the forest was quiet. A few birds chirped but the woodpeckers who had carved out standing pillars of dead tree trunks could not be heard.

The small cemetery appeared amongst the trees at the top of a hill. In 1977, as part of the sesquicentennial celebrations of the first township council meeting, which was a very big deal locally, residents repaired this site. The four white stones that remained of the Bury family who had come to mouth of Clear Creek in 1816 had been broken since the burials there in the 1840’s and 50’s. Each soft-looking white marble stone had been decorated with a Weeping Willow tree, symbolizing life after death and the resurrection of the soul. Names, dates of death and length of life and family relationships were chiseled below. Some important facts had been lost through breakage and scattering of stone pieces.

The first white family settled at Clear Creek in 1816. Their cemetery is hidden on the edge of Clear Creek Forest Park.

Now, the stones were rearranged like puzzle pieces and parged into the face of angled-back concrete wall. The wall is less than four feet high and 12 feet long. It is two feet thick at the top sloping out to three feet wide at the bottom.

The new concrete wall faces east, looking over a valley that is sliced at the bottom by a narrow stream. A few feet to the south of the stones, the hill slopes down to a small river flat. The Clear Creek Forest which envelopes the burial site, is public parkland owned by the Nature Conservancy of Canada, so we walked down the hill. The area was well covered with long grasses of abandoned pastures and sedges. Eager Toad Lily leaves emerged purple and green along the exposed borders of deer trails. The odd hawthorn tree had sprung up in this patch. Unfortunately, I placed my hand casually on a raspy trunk and was stabbed by one of its ubiquitous thorns. Large ash trees, defeated by the Emerald Ash Borer had crashed onto the flats. Their straight, round trunks dispersing into dust. Cutting the flats in half was the serpentine edge of Clear Creek. Grass and tree roots hung out over the clay banks that were sheared and exposed for at least a meter and more high. At the bottom, the clear water was only a few inches deep and about eight feet wide. It tinkled and giggled as it burbled over the small rounded stones on creek bed. There was one larger rock that appeared to have been squared as if for a buildings foundation. The water moved faster around and over top of it. On the other side or the creek, the valley walls rose up and disappeared into tree roots.

Clear Creek cuts through the clay banks as it meanders through Clear Creek Forest to Lake Erie at the municipal Clearville Park.

I walked north along the edge of the creek, listening to the water and met Manfred at the base of the hill. We ignored the gently angled muddy deer track and climbed straight to the edge of the gravesites. Where their homes or barn or fields were located is hard to tell without further investigation. Who and what came before them is not marked. And what came after them is scantily recalled in history books

The stones represent a moment in time, when the first white family who settled in this township, lived and died.

Susanne Spence Wilkins, April 2022